Patients may feel they are letting the doctors down if they don’t accept the treatment offered – but, says Louisa Nicoll, maybe changing the thinking to “just because you can, doesn’t mean you have to” could be something to consider.

John and Louisa

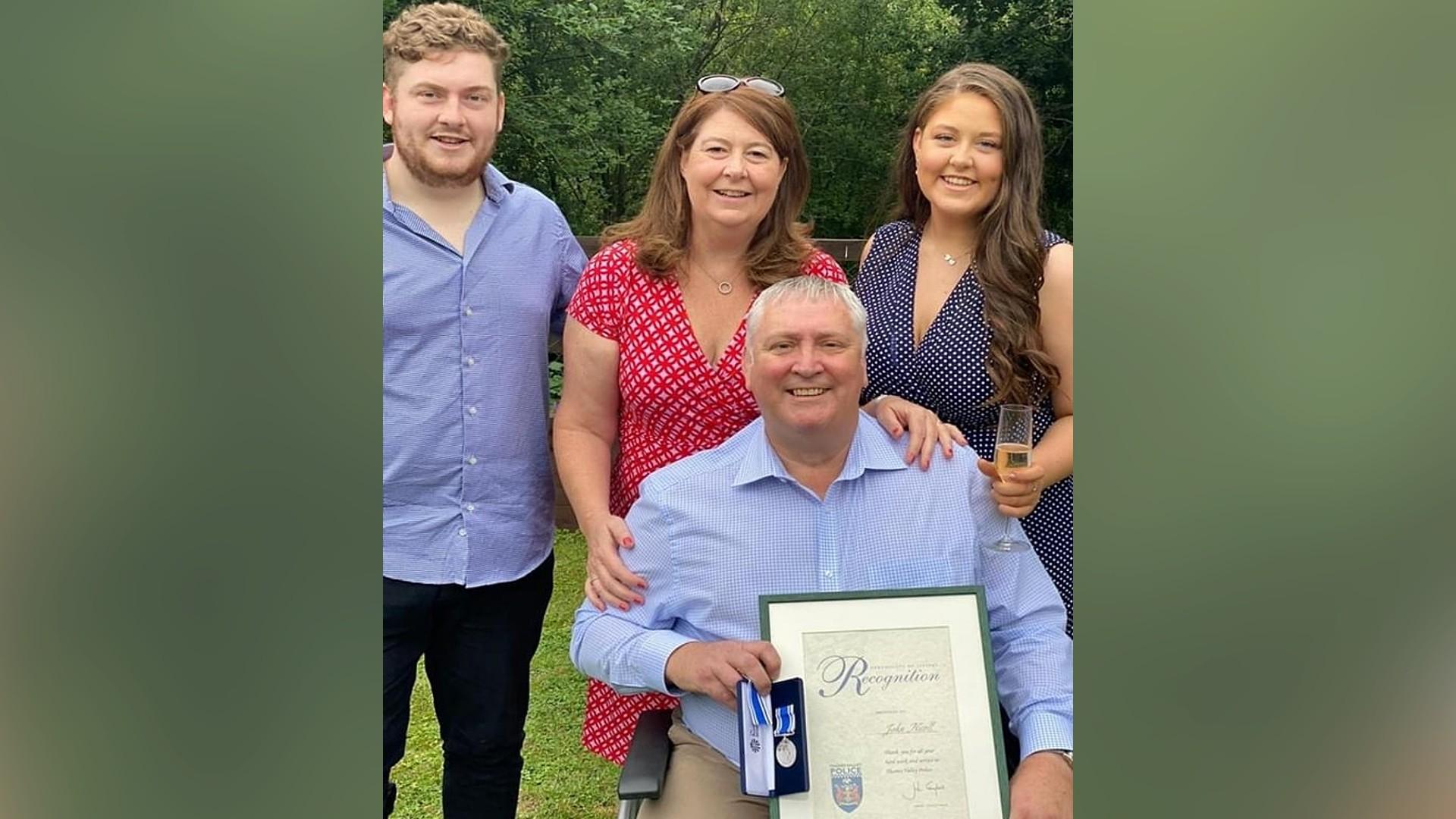

Louisa and her husband John were living a happy life in Berkshire with their two teenage children when John received a cancer diagnosis. However, after four years of physically and mentally draining treatment the disease was no longer responding.

Eventually, John chose to forego palliative chemotherapy, and instead focus on the quality of the end of his life. Louisa tells their #DyingMatters story.

A harsh reality

“Never in my professional career had I imagined this would happen to us.”

Having worked as a clinical nurse specialist and hospice ward manager, Louisa was used to supporting people at the end of their lives, and their families. But in the midst of a global pandemic, it was now her turn to go through the experience, as her husband John entered the last few months of his life.

“There is nothing more likely to focus your thoughts on what is important in your life than hearing your life expectancy being predicted in months.”

Six months beforehand, in a cramped clinic room, on an October afternoon, John and Louisa were told by the oncologist that John’s disease was too advanced for further surgery. They gave him a life expectancy of up to 18 months with palliative chemotherapy – and perhaps just 12 months without it.

“John had hated chemo – he said he wouldn’t go through it again even if his life depended on it – but here we were today… it seemed like his life did depend on it. How different you feel when faced with this harsh reality.”

Without much time for discussion, John signed a consent form to start the treatment – which Louisa bleakly describes as ‘being back on the rollercoaster’.

‘Our greatest protector’

Born in Dundee in 1965, John moved to London in the mid-1980s to begin a career with the Metropolitan Police service, later to transfer to Thames Valley – over 30 years in a career of which he was extremely proud.

John and Louisa met in 1991 and married in 1994; their son James was born in 1997, and daughter Amy in 2001.

Louisa describes John as “a wonderful husband…he had a great sense of humour and always put people at ease”.

A badly given diagnosis

The initial symptoms of John’s osteosarcoma were first spotted in September 2015, but not diagnosed until the following March. John was told over the phone, while he was at work, and without Louisa present. As far as breaking bad news goes, Louisa says, "it couldn’t have been worse".

Over the next 4 and a half years, John underwent a number of painful and intrusive operations, including an above the knee amputation and a thoracotomy; in addition to four cycles of chemotherapy and ‘countless’ hospital appointments.

The choice

When John and Louisa were presented with the recommendation from the doctors that John be given palliative chemotherapy, it kickstarted a series of conversations between them as to whether there might be a better way forward. Louisa explains:

“One evening, John told me he was only having the chemo for me and the children – if he had a choice he wouldn’t have it – but in reality he did have a choice. We started talking about what was really important to him and to us as a family – what really mattered most.”

Chemo: ‘a very chaotic time in our lives’

It was the heart-breaking effects of undergoing treatment that eventually made John’s decision easier – and is something Louisa feels is ‘under-discussed’ in clinical care.

“The disruption that chemotherapy causes to a person and their family – three nights in hospital every few weeks – isn’t quite the whole story; there are investigations beforehand, often delays and sometimes cancellations. Seeing the side effects written down on a leaflet is so very different to experiencing them, and they are debilitating. The time John had chemo was a very chaotic time in our lives.”

After much thought, discussion and many sleepless nights, Louisa says that in the end, John’s decision came down to this: the burden of symptoms and disruption for potentially living just six months longer was simply not worth it.

"John hated time in hospital, being away from his family and work, and found being a patient stripped him of his identity and dignity."

‘It’s a bit sooner than we would normally do’

When the oncologist told John and Louisa in October 2019 that the treatment options available to John would only be palliative, they asked if he could be referred to palliative care services instead. Louisa says that the response they received surprised them: “it’s a bit sooner than we would normally do.”

Louisa adds, “it’s interesting that although the direction of treatment had changed to palliative, there was a reluctance to involve palliative care – yet when John had cardiac or renal issues, and lung disease, the referrals to the specialist teams happened almost immediately.”

“Oncology clinics are busy places and clinicians have a heavy workload. Patients often don’t have time to digest information or know the questions to ask. A more integrated service between oncology and palliative care would certainly have been beneficial to us, and I suspect many others.”

In a phone call with John’s oncologist, John reiterated his wishes against having any systemic treatment. It ended with the consultant reassuring John that he was ‘making all the right decisions’.

"We had talked it through with our children, as they were fully aware of the situation by now and they completely agreed – they just wanted life to be calm and for us to spend time together as a family – we had all experienced a very disruptive time in all our lives.”

The human built-in chip for survival

With years of experience in the palliative care and clinical worlds, it was Louisa’s knowledge of advanced care that enabled her to engage with clinical colleagues and explore the thinking around end of life treatment and care.

“After John died I spoke to his Consultant who said it was unusual for a patient to decline treatment from the start – often they will stop after two or three cycles when they find it hard to cope with the toxicity.”

“I wonder how many of those patients would have preferred an honest conversation at the beginning and not endured those months of treatment?”

Louisa shared John’s decision with Sarcoma clinicians and they echoed her thoughts:

One said, "it sounded like the right decision has been made. I think it is often harder to say no to treatment, maybe it is because a doctor is offering it, and there is the human built in chip for survival. Looking back I wish more people perhaps felt able to make the decision you and John have made, I think they would have had more living time.“

Hope changed over time

Louisa says John worried that people might have felt like he was giving up, but he was actually giving it his all. “The new-found sense of calmness allowed him to concentrate on living well for as long as he could. He didn’t give up hope, but the hope just changed over time.”

John’s work gave him a sense of purpose, routine and normality with colleagues who were incredibly supportive throughout. He continued working full-time until March 2020, when, Louisa says, despite all their best plans, “we had not factored in a global pandemic.”

John's decision cleared a path for the family to focus on enjoying the time they had left together: family weekends away, 18th birthdays, Christmas celebrations, and trips to visit friends and family. It was these memories that helped John’s family cope after he died.

Adding life to his remaining days

In a touchingly thoughtful memory, Louisa says that John spent time in lockdown writing letters for friends and family to open after he died, and produced an 18 page ‘Life Story’. He created ‘the most wonderful document’ for Louisa, titled “Things You Should Know” with details of accounts, logins, passwords, and dates for the cars’ MOTs.

He even wrote Christmas and birthday cards for Louisa and their children to open for the next three years.

Louisa says that John felt that the lockdown was robbing him of time with friends and the wider family.

Once restrictions lifted, John made it his mission to see as many of them as possible: his family and school friends from Scotland visited, and we had many lovely lunches and evenings spent with people that had been important in John’s life.

Louisa adds, “we also had a very special day when the Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police presented John with his long service award in our garden just weeks before he died. He certainly added life to his remaining days.”

“How people die remains in the memory of those who live on”

This quote by Dame Cicely Saunders – widely known as the founder of modern day hospice care – wouldn’t have been known by John, according to Louisa.

But, she says, “I believe making the decision to decline chemotherapy gave John control over how he lived the rest of his life and we created better memories in our last months together because of it.”

At John’s funeral, their son, James, added that his dad would have wanted to leave an impact after he died: “if it could be my Dad’s legacy to stare death in the face, and be calm and organised to make life easier for loved ones then I think he would be very happy, and I would urge others to do the same if presented with the situation.”

Telling his story

Louisa adds a final memory, of the day that she and John were sat in the garden discussing what she would do about work in the future:

“He said ‘I think you’ll tell our story – even if it helps just one other family to know that it is possible to live a good life when faced with dying’.”

Thank you to Louisa for sharing her – and John’s – story.

This article is based on a presentation made by Louisa Nicoll to British Sarcoma Conference at ICC Wales in March 2023 and adapted for Dying Matters and Hospice UK.

Dying Matters stories

Read more real Dying Matters stories from people who have experienced grief and bereavement.